|

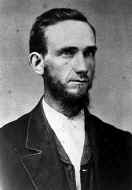

D. M. CanrightTHE MAN WHO BOARDED THE PHANTOM SHIPPart 4 D. W. Reavis, who had been a lifelong friend of Canright, tells of his last interview with him. The date was 1903. (You will recall that Reavis was the one who, in the fall of 1880, told Canright in a lonely park in Chicago that if he ever left the message, he would return to nothing.) "All the years intervening between the time of our Chicago association in 1880, and 1903, I occasionally corresponded with Elder Canright, always attempting to do all in my power to save him from wrecking his life and injuring the cause he had done so much to build up. At times I felt hopeful, but every time my encouragement was smothered in still blacker clouds. "I finally prevailed upon him to attend a general meeting of our workers in Battle Creek in 1903, with the view of meeting many of the old workers and having a heart-to-heart talk together. He was delighted with the reception given him by all the old workers, and greatly pleased with the cordiality of the new workers. All through the meetings he would laugh with his eyes full of tears. The poor man seemed to exist simultaneously in two distinct parts—uncontrollable joy and relentless grief. "Finally when he came to the Review and Herald office, where I was then working, to tell me good-by before returning to his home in Grand Rapids, Michigan, we went back in a dark storeroom alone to have a talk, and we spent a long time there in this last personal, heart-to-heart visit. I reminded him of what I had told him years before in Chicago, and he frankly admitted that what I predicted had come to pass, and that he wished the past could be blotted out and that he was back in our work just as he was at the beginning, before any ruinous thoughts of himself had entered his heart. "I tried to get him to say to the workers there assembled just what he had said to me, assuring him that they would be glad to forgive all and to take him back in full confidence. I never heard any one weep and moan in such deep contrition as that once leading light in our message did. It was heartbreaking even to hear him, He said he wished he could come back to the fold as I suggested, but after long, heartbreaking moans and weeping, be said: ‘I would be glad to come back, but I can’t! It’s too late! I am forever gone! Gone!’ As he wept on my shoulder, he thanked me for all I had tried to do to save him from that sad hour. He said, ‘D. W. whatever you do, don’t ever fight the message. — D. W. Reavis, in "I Remember," pages 119-120. It was in 1904, that Elder George I. Butler, now President of the Southern Union Conference, wrote a warning to John Harvey Kellogg, in which he referred to Canright’s present status: "Poor Canright, where is he? If ever I pitied a man, I do him. He looks to me like a poor, seedy, used up old man, and he thought he was going to do grand missionary work . . No man in the Cause, believing . . as you have believed, can take your stand against what the Testimonies say and maintain your spirituality." —G. I. Butler, Letter to J. H. Kellogg, dated August 12, 1904. Elder J. C. Harris, who was for many years a pastor in the Michigan Conference, had a conversation with Canright soon after the turn of the century. William J. Harris, his son, later wrote the incident down: "Some general meeting, a conference session, or some such type of general gathering, was being held in the old tabernacle at Battle Creek My father happened to meet Mr. Canright, who had come to meet some of the brethren. They knew each other fairly well and called each other by their given names. After a word or two upon meeting, my father said, ‘D. M., isn’t it about time for you to reconsider and get back into the faith before it is too late?’ ‘No, Jap’ (my father’s name was Jasper, but many called him ‘Jap’), said Mr. Canright, ‘No, I can never do that. The Holy Spirit has left me for good. I can never do that. My heart no longer feels the impression of the Spirit.’ "I have heard my father repeatedly tell this experience as he sought to warn people of the danger of rejecting the appeals of the Holy Spirit to their hearts."—William J. Harris, Statement to Arthur L. White, dated December 30, 1964. Less is known about the years 1904 through 1913, than about any other period in Canright’s life. It appears that during those years he intermittently turned to book-selling. Frequently these were Seventh-day Adventist books, and often they were the books written by James Edson White, Ellen White’s eldest son. During those years he lost his left eye. Blinding headaches, traceable to this eye, became worse, and he was finally told by a surgeon in Ann Arbor, Michigan, that if he were willing to lose his left eye he might save the other. It was explained to him that the operation might prove to be fatal. He was later to mention in correspondence to Madge Knevals Goodrich, writer for the "Baptist Herald," that during the operation he had no assurance of coming out of it alive, or of being saved if he didn’t! During the operation, his left eye, together with the facial nerves around it, were removed. This left him with a sunken eye socket. And since he never did anything thereafter to hide it, his appearance was, frankly, repulsive for the remainder of his life. Gradually his finances waned still more. He barely made it in door-to-door selling, even with his wife selling also. The royalties from his books dropped off as interest in them declined. A little money came from his farm but, as he was to recount to W. E. Cornell in May of 1913, it was "a sand hill." About the year 1912, Miss Florence E. Ransaw, who at the time was living in Otsego, witnessed the following experience: "While we were yet living in Otsego, Mother and I went to church one Sabbath. The church was full of people that Sabbath, as we had a visiting minister, an elderly man. I don’t remember his name now. He preached a powerful sermon; it sank deep in every heart. All during the sermon I could hear some one stepping around in the entry-way as the door from the entry-way into the church was open some six or eight inches. I supposed it was some mother trying to keep her child quiet during the meeting as they often did. But instead it was D. M. Canright that was out there all during the sermon, and he surely heard a wonderfully good sermon. "As soon as the minister finished and sat down, and the elder of the church announced the closing hymn, —in walked Elder Canright briskly up the center aisle to the front of the church and facing the audience said, ‘I don’t think I need any introduction. I think you all know who I am—D. M. Canright. I love this church. I love this people—I got my first wife out of this church and a better woman never lived—I love this church, I love this people and by rights this is where I belong. "All the while he was speaking he was weeping, using his handkerchief freely. . Then the minister spoke up and said, ‘Well, brother, if that is the way you feel you had better come back to us. "Elder Canright turned to the minister and said, ‘I can’t I’ve gone too far.’ Then he sank down on the front seat weeping and was still sitting there when we left the church."—Florence E. Ransaw, Letter to J. H. Rhoads, written from Charlotte, Michigan, dated August 26, 1958. At some time during the next year (1913), Canright, who by then was living in Battle Creek, stopped to visit at the home of Sister Howe. She lived a couple of blocks from the Dime Tabernacle. It seems that Canright was trying to sell books and apparently did not know that she was an Adventist. Elder Clinton Lee, who was living in Battle Creek at the time tells what took place: ‘How do you do, Elder Canright,’ she said in response to his knock at the door. She invited him in. ‘Do you know me?’ he asked. ‘Indeed, I do,’ she replied. "After they had talked for a time she asked, ‘Why don’t you come back to the church?’ "His reply, spoken in tones of unutterable sadness was: ‘Sister, it is too late. "With every gesture denoting despair he arose and walked out the door, the words ‘Too late, - too late, ‘like an echo, following him as he made his slow way down the street. "Elder Lee remembers seeing Canright only once, when he walked quietly into a workers’ meeting at Grand Rapids. Whenever possible, this seemed to be Canright’s custom during the years 1910-1916. He especially enjoyed attending meetings of Seventh-day Adventist ministers. When Canright was pointed out to Brother Lee, the young minister observed that he had only one eye, the result of surgery. Everyone noticed how pleased he was to meet with some of his former brethren." Poor Dudley seemed to be a man without a home—who knew where it was, but unable to return to it. And yet, as we have observed, he often went where Adventists gathered so that he could be among them. And on occasion, he freely admitted that he had made a mistake in leaving the message and the Church and that he ought to come back, if somehow he knew how to. But there seemed to be a strange power that kept him from returning. And yet, paradoxically, although he did not mind Adventists knowing the truth of the situation, he would write raging letters of denial if a query came from a non-Adventist who had learned about his words and actions. As rumors spread that he regretted having left the Adventists, he would write and publish heated denials. And he would repeat these to his relatives and to Baptist friends. On one occasion he had such a statement notarized and published in the public press, with the hope that this would squelch the rumors. Although the truth would be forced out of him at times, yet he feared losing the royalties on his attacks against Adventism. Thus, we find contradictory statements by Canright. He had become something like the fictional character. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, first soft and tender, and then violent and malevolent. We have now come into the year 1913. It would be well at this point to give attention to the experience of Carrie Shasky. Recently, her family had moved to Battle Creek and her mother had passed away. So Carrie, upon being baptized, was now on her own. For several weeks she worked in the kitchen of the large Battle Creek Sanitarium. In order to better understand the story, you will need to keep in mind that by 1913 Dr. Kellogg had separated the Sanitarium from the Adventist Church. He himself was no longer an Adventist. Although it employed many Adventists, yet, under his management, the Sanitarium was in no way connected with the Church. "While working in the Sanitarium kitchen she noticed from time to time that a tall poorly clad elderly gentleman would come in the back door of the kitchen. He stood straight, and his bearing indicated that he had been a man of some distinction. He carried a courtesy meal ticket and he would sit at the corner of a worktable [in the kitchen]. Someone would fix up a tray for him and take it to him. At times I fixed the tray. His uncut hair, his untrimmed and dirty fingernails, his unkempt attire, the absence of one eye, made this stranger somewhat repulsive to the girls who waited upon him. We were all curious to know who he was, but no one seemed to know. We called him ‘Mr. X.’ All we knew was that we did not enjoy his presence in the helpers’ kitchen, and that he entered and left by the back door."—Carrie Shasky Johnson, "I Was Canright’s Secretary," page 119. [Hereinafter, this volume will be referred to as "IWCS."] At this time, Canright’s wife, Lucy, was nearing her end. Where she was at this time we do not know. After working in the San kitchen for several weeks, Carrie enrolled at the Battle Creek Business College. It was managed by a Mr. W. E. Cornell, who had earlier been an Adventist, and apparently returned to the Church in later years. But at this time he was out of the Church, and so in a position to be sympathetic to helping Canright in his writing work. Cornell had agreed to let Carrie take course work, with the proviso that she repay it later on when she might have employment elsewhere. Then, on January 2, 1913, Lucy Hadden Canright passed to her rest in Grand Rapids. D. M. was disconsolate. The man who was alone now seemed so much more alone. He feared that the experience would result in his own death, and so he journeyed down to Battle Creek in the hope that the Amadons would let him stay with them. (The Amadons were life-long Adventist workers who had known and befriended Canright and his family for years.) But arriving there he learned that Martha Amadon was living with relatives and her husband George was dying. Martha urged the grief-stricken man to return to the Church. He replied, "I can’t; it is too late." (IWCS, 123) She then told him to go see Cornell, which he did. Cornell contacted J. H. Kellogg who provided Canright with a cottage room at no charge, and, again, a daily meal ticket at the San kitchen. He then told Carrie that she could work off the bill she owed on her schooling by doing secretarial work for Canright. "After being sworn to secrecy, I was told that I was to work for a former prominent Seventh-day Adventist minister. Mr. Cornell told me that he himself had been his first secretary [years before] and that I would be his last secretary. I was reminded that I should not reveal what was said or done or for whom I was to work."—IWCS, 120. "I was petrified in Mr. Cornell’s office as I was introduced to D. M. Canright. I recognized with consternation that my new boss, ‘the former prominent Seventh-day Adventist,’ was none other than the familiar ‘Mr. X’ whom I had seen in the helpers’ kitchen."—IWCS, 120-121. Canright was given the free use of an unused office room in Cornell’s business college. It had an outside door so that both Canright and Carrie could enter and work unobserved while she did secretarial work for him. Her first assignment, that day, was to take dictation on and then type up newspaper obituary notices about his wife, who had just died that morning. After that, they got into a gradual routine of office work. It primarily included replying to mail and preparing a book manuscript for Canright’s next book, "The Lord’s Day From Neither Catholics nor Pagans." Occasionally, Canright was away and she could do piecework in the Sanitarium College library—and make enough to almost, but not quite, meet her own living expenses. Canright did not keep regular hours, which was a hindrance to Carrie. Supposed to be working off her business school expenses, she would come and wait in the office room, when she could have been doing piecemeal work at the library. Canright could have notified her the day before when he would be absent, but he did not do this. Learning about this, Cornell would become irritated and confront Canright about the matter, but each time he would plead all his woes and problems, and everything would continue on pretty much as before. "I remember that Mr. Canright had some copies of Elder J. E. White’s books ‘Gospel Primer’ and ‘Best Stories from the Best Book’ besides Bibles . . I asked him one day why he didn’t canvass in Grand Rapids and live at home. He replied, ‘I’m a Baptist in Grand Rapids. These books do not have so ready a sale there as in Battle Creek. Battle Creek is stuffed with Adventists. They are the people who buy these books and Bibles.’— IWCS, 126-127. Because his financial situation kept dropping lower, Cornell, together with Drs. Kellogg and Stewart, decided it would be well to send Canright to unite with and, hopefully, strengthen an offshoot organization in Lincoln, Nebraska, that they apparently favored. Albion F. Ballenger, John F. Ballenger, M E. Kellogg, A. T. Jones and a man named Ruppert were there publishing a journal entitled, "The Gathering Call," in the pathetic hope that somehow if they could get all the Adventists out of the Church, and following them, all the problems of life would be solved. Since Cornell, Kellogg and Stewart were Canright’s financial backers in Battle Creek, he dared not disagree with them, so off he went on the train to Lincoln. By now it was late April, 1913. But before long he was back again. "He was tired and discouraged. As he sat in Mr. Cornell’s office he told us [Carrie was present] that John F. Ballenger, who had headed ‘The Gathering Call,’ had died; that M. E. Kellogg, A. T. Jones, A. F. Ballenger, and Elder Ruppert were quarreling among themselves. He further said that ‘The Gathering Call’ was about to be moved to California, and that they had no vacancy for him. "He now poured out his lamentations. In substance he declared, ‘I’m a man without a home. My daughters Bessie and Nellie are school-teaching. They stay with their half-sister, Genevieve [Veva] who lives in Hillsdale and is having a hard time maintaining a home for her son, who is in college, and her two half-sisters. I am welcome there, but I can’t put another burden on her. "I have no way of maintaining myself. The royalties on my books have run out. The farm is a sand hill. I can’t raise much on it, neither can I rent it profitably.’ "Mr. Cornell questioned him about the Baptists. "With tears in his eyes he replied, ‘The Baptists here in Battle Creek have provided me with a key to the church basement and with an old desk in a corner. I can go and come there at will, and at Grand Rapids they have honored me with the title of ‘Pastor Emeritus.’ But they say I am too shabby and don’t grace the Baptist dignity, so they don’t contribute to my support. I am virtually rejected by the Baptists. ‘The Adventists still owe me something for all the work I did for them and all the money I raised. There are the fund-raising projects I promoted, which they still use. "‘My daughter Nellie is a Christian Scientist and a practitioner for the Christian Scientist people. All the girls follow Christian Science. Jasper is in the country; his wife is sick; I can’t go there. My cousin, Theodore, lives in town; I don’t get along with him; I can’t stay there. I have no money to get a glass eye or suitable clothing.’ "I later learned that adverse financial conditions had prevailed for years, and that for two years prior to his wife’s death he had been unable to maintain their household. His wife had lived with her brother’s family, and had sustained herself by door-to-door selling of Adventist children’s books."—IWCS, 128. So the old secretarial arrangement began again for Carrie. Her first assignment was to take dictation for an obituary request to D. W. Reavis with the hope that it might be inserted in the "Review." Carrie was surprised at this, but soon realized that Canright’s plan was to seem friendly enough to the leaders that they would invite him to the General Conference Session which would convene on May 15 in Washington D.C. When he was not writing articles fighting the Adventist message and people, he was yearning to be back with them. The obituary was published, but he received no call to attend the Session. He appreciated Reavis’ reply and responded to it with a comment of how much he appreciated Seventh-day Adventist doctrines. He then concluded with a picture of his present prosperous condition: "I am perfectly well in body and in mind, just as active as ever. Have a beautiful home, worth $10,000 or $12,000 [equivalent to $70,000 to 90,000 today]. Everything I need and a lovely family of children. The Baptist Church here [he used his Grand Rapids address on his correspondence] , of which I have been pastor twice, always an active member, revere me as their father, and consult me on all important things. My decision on any doctrinal questions settles it - . I am now 72 years old."—IWCS, 132-133. If you are one of those inclined to think, as does Walter Martin, that everything that Canright said was the truth, reread the above paragraph. Prior to the trip to Lincoln, much of Canright’s dictation to Carrie was material for his anti-Sabbath book, mentioned above, a revised introduction for a new printing of "Seventh-day Adventism Renounced," and daily correspondence. But after his return, the main bookwork was the dictating of chapters for what was to be his last book, "Life of Mrs. E. G. White," in which he violently attacked her character. "When he was dictating personal letters, I usually sat opposite his desk. At such times he was calm, composed, and had a note of assurance in his voice. Occasionally he would come to some point in his dictating in which he referred to Mrs. White. Strange as it may seem, his references, made almost inadvertently it seemed, were often favorable. But when he then turned to his work on the "Life of Mrs. E. G. White" he would become harsh, vindictive, belligerent, and unreasonable. "I have seen him on a number of occasions, when he would come, as it were, to a climax in his dictating on the life of Mrs. White, totally exhausted, tears flowing from his good eye as well as from the open socket while he wept bitterly. At such times I have seen him drop in his chair by his desk, and momentarily bury his face in his arms on the desk. Then as he swung his left arm in a gesture of utter despair, he would exclaim with three inflections, each more pathetic than the one before, ‘I’m a lost man! I’m a lost man! I’m a lost man!’ Frequently he would add, ‘She was a good woman! I am gone! gone! gone!’ "It was almost more than I could take. As a result I decided to take his dictation with my back turned to him, without having to witness his anguish. In this way I was able to proceed with my work."—IWCS, 134-135. Canright knew he was dictating lies about Ellen White for this book, as he had dictated lies about Adventists and their doctrines for his preceding books. A step in the wrong direction leads to more wrong steps. And Canright knew he was well along the path to perdition. But he could not break the chains that held him. To do so would require public acknowledgment of his lying words to the non-Adventist world, and he could not bring himself to do this. To do so would be to stop his last source of "admiration. "The force of what seemed to me to be his repeated appeals for help weighed heavily upon my emotions, and I longed to go to the Tabernacle and ask for help from the ministers in charge. But I felt I must not do this. I was bound by a pledge to secrecy and my loyalty to Mr. Cornell. I felt I could not reveal what I saw or heard to anyone in or out of the office."— IWCS, 135. But mingled with this despair, was a desire to learn about and be with the only people in the world that he believed had the truth. If he could not live with them in heaven, at least he could enjoy being near them on earth. "I kept Mr. Canright informed in regard to Adventist meetings. Somehow he seemed to enjoy the prospect of attending Sabbath services, prayer meetings, and church functions. He made repeated attempts through me to secure invitations to church board meetings and other business meetings. His eagerness in this respect led some Adventists to believe he had returned to his former faith, or at least was in the process of doing so. But Mr. Canright’s frequent remark when urged to do so was, ‘Oh, I want to, but I can’t; it’s too late!’ "I often witnessed and heard the bitter lamentations he uttered at times. Then I would see his mood change. Sometimes this would take place within minutes, and the same old belligerent attitude would be manifested again."—IWCS, 135. For a few minutes, Canright would cry out from between the chains. But then the demons would coax him into a proud antagonism and he would be held down again. There is a sense of power in the moment of expressed pride. This was Canright’s undoing. He was unwilling to say good-by to that spirit. Carrie, who regularly attended services at the Tabernacle, mentions that Canright would frequently attend the 11 o’clock services there. "As a rule, however, Mr. Canright chose to enter just as the first song was announced. He always seemed to come with his small brown satchel in hand and he would march clear down next to the front pew. On more than one occasion when prayer was announced and the congregation began to kneel, I have seen Mr. Canright make as if to kneel, but seemed unable to do so. Sometimes he would wave his right arm, and utter a distressed cry. ‘Don’t let me fall, brethren, don’t let me fall!’ The deacons would then hurry to his aid, thinking he was ill, and would assist him outside. When he would reach the vestibule he would walk away on his own. "One Sabbath morning, thinking that perhaps he had left the Tabernacle in order to attend services in the Seventh Day Baptist Church about four blocks away, I followed him to see. But his journey only led to the cottage behind the helpers’ kitchen [at the Sanitarium] where he stayed."—IWCS, 136. Canright would also attend prayer meetings, arranged by Tabernacle personnel, in the community. "At the cottage prayer meetings he would usually linger in the yard or on the porch until the first song was announced. Then he would enter with his little satchel. Oftentimes Mr. Canright’s attitudes, his repudiations, his confessions, and the statements such as ‘I’m a lost man,’ or ‘She was a good woman,’ were freely discussed at these prayer meetings, and just as often heartfelt prayers were offered in his behalf. "But when reports of his confessions and statements leaked out, Mr. Canright would hasten to make public denial through the press. One day he dictated the following statement to me, which eventually appeared in his book, ‘Life of Mrs. E. G. White:’ "‘MY PRESENT STANDING—Since I withdrew from the Adventists, over thirty years ago, they have continued to report that I have regretted leaving them, have tried to get back again, have repudiated my book which I wrote and have confessed that I am now a lost man. There has never been a word of truth in any of these reports. I expect them to report that I recanted on my deathbed. All this is done to hinder the influence of my books. I now reaffirm all that I have written in my books and tracts against that doctrine . . —D.M. Canright.’ "He used this statement, with some additions, again and again."— IWCS, 136-137. As we have seen, there is "a great cloud of witnesses" that tell what really took place back at that time. Sincere Christians who, over the years, wrote down what they saw take place. Such testimonies are to be found in abundance in the present historical study you are now reading. The truth is that under the continual goading of demons, Canright, in the preparation of his books, became a hardened liar,—hardened by devil-possession. "It always seemed strange to me that he should write vehement denials for the press, when I daily witnessed in private the very things he publicly denied. At times he seemed to realize that he was possessed by a power over which he had no control. An overwhelming desire for peace of mind seemed to dominate his subconsciousness. He yearned to be free from whatever power it was that controlled him. He longed for the warmth of companionship of his former Seventh-day Adventist associates. But he seemed unable to obtain relief. "He seemed to desperately want a way out of the fog. He seemed to sense that there were forces operating in his life that led him to do and say things at one time, which he felt grieved about at other times. The fact that he had seemingly lost his power of choice plagued him. Yet to my knowledge Mr. Canright never did admit even to his closest friends the fact that he had lost his power of personal choice or decision."—IWCS, 137-138. At first, Canright would hand anti-Adventist tracts to Carrie to enclose with the letters that she typed to mail out. But later he let her select from among them for something to enclose. "One day while looking for tracts I had discovered a pigeonhole near the place where Mr. Canright kept leaflets, which contained a little pile of tracts entitled ‘Elihu on the Sabbath.’ Not being acquainted with their authorship or content at the time, I one day enclosed these with the form letter rather than the Canright tracts. Several days later two or three of these letters were returned marked ‘Insufficient Address.’ Mr. Canright opened them, and out dropped the Sabbath tracts—tracts I was later to learn were published by Seventh-day Adventists [in defense of the Bible Sabbath] - I expected to be rebuked for sending letters out without giving the full and proper address. But again something incredible happened. He looked at the tracts, recognized them as Seventh-day Adventist productions defending the Seventh-day Sabbath, and said, ‘This is what I really wanted enclosed, but I couldn’t say it that way.’ It left me puzzled. "Repeatedly while I was Mr. Canright’s secretary, I heard him say one thing, as though under the control of some invisible power, while at other times I have heard him openly confess that he felt quite differently. "After the above-mentioned incident took place, and while receiving dictation adverse to Mrs. White, I sometimes would inquire, perhaps impertinently, whether that was really the way he wanted to say it. On such occasions he would sometimes reply, ‘What I want to say, I can’t.’ IWCS, 138. Another fabrication of Canright’s were the "testimonials" that appeared in his books and newspaper articles. These were purportedly penned by leading citizens and influential Protestants and Baptists. Canright would write out glowing reports on how wonderful Canright was, then he would send them to various individuals in the hope that they would sign and return them. Enough came+ back to enable Canright to keep up appearances of success and greatness in the public eye. During the time that Carrie was with him, he would dictate the testimonials to her, and then instruct her who the typed copies should be mailed to for their signatures. "Many of the complimentary articles that appeared in newspapers, church organs, broadsides, and testimonials were written by Mr. Canright himself and prepared for the promotion of his literary productions. In his testimonials, a number of which I wrote at his dictation, he named many of the finer virtues and talents which he thought he possessed. These I sent at his behest to those whose signatures he believed would carry more weight. The careful reader may detect the characteristic Canright style in many of these testimonials and note the repetition of certain typical words and expressions. He may also observe that those who signed the testimonials could hardly have been in possession of all the points of information presented, such as details concerning Canright’s work while a Seventh-day Adventist."—IWCS, 138-139. As his secretary, Carrie noticed that Canright usually carried copies of the "Review" in his pocket, and that, when in the office he read from them, tears would come to his eyes. Articles that especially affected him, Carrie would later look up and read. They usually dealt with the progress of the Advent Movement and the successful evangelistic and missionary work of former associates of his. Finally, one hot day in July, 1913, as Carrie was going home to lunch, she stopped in at the Tabernacle to pay her tithe—three dimes. Two ministers were present and they began questioning her, and the entire story came out. "Both of them were officers of the church, and they showed sympathy and understanding. I answered simply and briefly. My replies increased their interest. Before I realized it, I had told them all I knew. The circumstances and the heavy burdens that rested on my youthful shoulders dispelled for the moment any thoughts of loyalty either to Mr. Canright or to Mr. Cornell. "The men told me not to be in a hurry [to go home for lunch] -They counseled between themselves, and then in my hearing Mr. Israel said to Mr. Minier, ‘This girl is in danger. Can’t you do something about it?’ Mr. Minier replied, ‘I think something can be done, but when?’ "They seemed to think that if something was to be done, it must be at once. Mr. Israel then concluded the interview, stressing that I should act at once to terminate my services to Mr. Canright. He ended by saying, ‘I’ll get you a job if I have to pay you out of my own pocket.’"—IWCS, 146-147. Carrie had told them that Canright would not be in the office during lunch-hour, so they sent her over there immediately to gather her things together and bring them to the Tabernacle office and store them there temporarily. She immediately quit the Business College at the same time. A job was then obtained for her at the Battle Creek Food Company. Within a few weeks she was offered, and accepted, a position as secretary to the new President of the Southern Illinois Conference [now the Illinois Conference]. Leaving Battle Creek by train, she moved to Springfield, Illinois. Later she married the Secretary-Treasurer of the Conference, Frank Johnson. Later, she wrote a book about her experience, entitled "I Was Canright’s Secretary," which, unfortunately is no longer in print. As we have seen, in those final years, D. M. had no hesitation about visiting with Adventist Church leaders. Elder F. M. Wilcox, for thirty-three years the editor-in-chief of the "Review," tells of one such incident: "I recall an interesting conversation which I had with D. M. Canright some time before his death. I was attending a general meeting held in Battle Creek, Michigan. Elder Canright was at the Sanitarium taking treatment. He attended some of our meetings. "One day I sat down beside him, and after a pleasant greeting we had the following conversation: ‘. . I have followed your work through the years, and have regretted to see that you have separated from your former brethren. I am now engaged in the ministry of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and I would like to ask what your counsel is to me. Shall I do as you have done?’ "He dropped his head and meditated for a full minute. Then he inquired, ‘. . Are you in difficulty with any of your brethren? ‘I said, ‘Not in any way. .’Then he said, ‘My counsel to you is to remain right where you are.’ "It seemed to me that this was significant advice from one who had spent years in fighting the cause which he once espoused. . He did not feel free to advise another to follow in his steps."—F.M. Wilcox, in "Review" for August 22, 1940. Early in the Spring of 1914 the following incident took place. Elder Sype tells the story: "Early Spring of 1914, there was a ministerial meeting held in Davenport, Iowa. I believe it was a Union meeting of all denominations who wished to attend. It continued for a few days and various guest speakers were there. Among them was D. M. Canright, who was to address the convention on how to meet Adventism. "Elder A. R. Ogden was then President of the Iowa Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. He was somewhat acquainted with Brother Canright and since this was a well-advertised meeting at which all denominations were welcome, he decided to attend and incidentally to meet Elder Canright. "Elder Canright met him and seemed absolutely delighted to see him. He clung to him as to a long lost brother and proposed that they stay together in the hotel, which they did. "Elder Canright was to give his talk at the convention the following day. When it came his time to speak, his talk was exactly like that of Balaam when he went to curse Israel. —It was a blessing instead of a curse. He told these ministers assembled that the Adventists were a wonderful Christian people, and that they would make a terrible mistake to approach the matter of Adventism in any other spirit than this. He then advised them that the best way to deal with the Adventists was to accept them as Christian brethren and to keep down all controversy with them. "—R. J. Sype, Letter, dated June 10, 1963. The local elder of the Davenport, Iowa, Church then asked Canright to speak at this local church the following Sabbath. Many years earlier, Canright had held evangelistic meetings in Iowa and so was acquainted with some of the older members. Here is the local elder’s report through H. O. Olson: "When Canright stepped up to the pulpit and faced the audience, he began to cry. For sometime he hid his face in his handkerchief and wept. After he composed himself, he said, ‘As I looked into the faces of my former brethren, I remembered former days. I remembered when Elder and Mrs. James White found me, a young man, a sinner, in the woods of New York State, and how they brought me to Christ and helped me to obtain preparation for the ministry. . I remember J. N. Andrews, Loughborough, Haskell, Uriah Smith, J. H. Waggoner, and others. Oh! those were happy days! I wish those days could return again. You have the truth. You are happier than any other people on earth. Remain true to your denomination!’ "After the service, he went to the door, and as he shook hands with the brethren he again appealed to them to be true to this message. —R. J. Sype Report, through H. O. Olson, dated June 10, 1963. And we appeal to you, out there, whoever you may be, who may have slipped away toward the edges of the Great Advent Message—the Three Angels’ Message,—and we appeal to you who may have been lured toward the "new theology" of Desmond Ford and those liberal college teachers among us, and their graduates, now in the work. Our appeal is to stay by the true message—historic Adventism. This is God’s will for your life, and it is D. M. Canright’s appeal to you also. Canright’s elderly mother died in Colorado in 1914. She loved the Advent Message and remained with it to the death. At the time that Canright’s "Seventh-day Adventism Renounced" came off the press in 1889, she wrote him and asked for a copy so she could read it. In reply, he said, "No, Mother . . It is not a book for you to read. It was not written for people like you. . No, Mother, I do not want to send the book to you." (Canright letter to his mother, Loretta Canright, 1889, quoted by W.A. Spicer, in "Review," of January 13, 1949). Spicer added: "She was one of the old-line Seventh-day Adventists, rich in Christian experience, happy in the blessed hope, the hope of the second coming of Christ to gather His people. . While our former minister [Canright] was representing to the people of the great churches that he was finding great blessing in being free from ‘legalism,’ as he called obedience to the commandments of God, would he not want this good old mother to have the same experience? Not at all. Apparently our old associate had no inclination to lead that mother of his into the new way. "—WA. Spicer, in "Review" of January 13, 1949. Even Canright recognized that the "new theology" wasn’t worth offering to his own mother. In 1915, Canright’s second book came off the press. It was entitled "The Lord’s Day From Neither Catholics nor Pagans." Not received very well, it soon went out of print. One interesting aspect of this volume was a testimonial, signed by A. J. Bush, the church clerk of the Berean Baptist Church in Grand Rapids. Twice in the statement, Canright is called "Elder Canright." This is, of course, strange in view of the fact that the Baptists address their ministers by the unscriptural term "Reverend." But Canright was well known to use this term in connection with himself after his break with Adventists. Carrie Shasky Johnson learned that the engraving on his grave stone: ELDER D. M. CANRIGHTSept. 22. 1840- May 12, 1919AN AUTHOR OF WORLD RENOWNwas penned by Canright himself prior to his death and given to the officiating undertaker in a sealed envelope. It contained the wording that was to be placed on the stone marker, when funds might become available to erect one. As "Elder Canright," he would be linked with the Adventists; as "Reverend Canright," he would be linked with the other Protestant churches. On July 16, 1915, Ellen White died. Repeatedly, she had pled with Canright to turn back from the road he was headed down, but without success. D. M. well knew that she was one of the best friends he had ever had. After a funeral service in California, her casket was carried by train to Battle Creek where, on July 24, a second funeral service was held in Battle Creek. A number of people observed Canright’s words and actions at that funeral. G. B. Thompson, an honor guard at the funeral, told of Canright’s uncontrollable grief at the bier. A man just behind him in line spoke to him to comfort him. In reply, Canright said to him: "She is saved,’ I am lost." (That individual shared that with an Adventist minister who recently shared it with the present writer.) There had been a long line of mourners. After following the line on up the first time, Canright suggested to his brother, Jasper, that they get in line and go on up again the second time. Jasper says: "My brother rested his hand on the side of the casket, and with tears rolling down his cheeks, he said brokenly, ‘There’s a noble Christian woman gone.’" Jasper Canright always remained faithful to the Advent Message. On February 24, 1931, writing from Battle Creek, Michigan, he wrote: "My brother, the late Elder D. M. Canright, often told me to remain true to the message. He said too: ‘If you give up the message, it will ruin your life.’ Many years ago in a public meeting at West LeRoy, where he had been called to oppose the work of a Seventh-day Adventist minister, he made the following statements: ‘I think I know why you have called me out here. You expect me to prove from the Bible that Sunday is the Sabbath, and that Saturday isn’t the Sabbath. Now I can’t prove from the Bible that Sunday is the Sabbath, for it isn’t there, and I think I can convince you that Saturday is not the Sabbath. [sic.]"—Jasper B. Canright, Letter to Elder S. E. Wight of Grand Rapids, Michigan, dated February 24, 1931. Early in 1915, L. H. Christian, President of the Lake Union Conference, visited Canright in his Grand Rapids home: "In 1915 I was urged to visit D. M. Canright, who at one time was prominent in our church. He lived then on a poor little farm near Grand Rapids, Michigan. He was eager to tell about his past experiences and seemed to regret that he had ever left the Advent people. He talked like a discouraged, disappointed man. As we talked about old-time Adventists, he began to tell about Mrs. White. "He said, ‘I knew her very well. For some time, as a young man, I lived in her home, and for eighteen years was intimately acquainted with the White family. I want to say to you that I never met a woman so godly and kind and at the same time so unselfish, helpful, and practical as Mrs. White. She was certainly a spiritual woman, a woman of prayer and deep faith in the Lord Jesus.’ "I asked him what he thought would happen to people if they followed the Testimonies of Mrs. White. "He answered, ‘Anyone who follows her writings, the Testimonies, as you call them, in prayer and faith will certainly get to heaven. She always exalted Jesus, and she taught true conversion and genuine sanctification as few others have. I have known a great many men and women who claim to be extraordinary in their imagined divine calling and gifts. I have always found them more or less arrogant and proud, eager to be recognized and often arbitrary and harsh in judging others. With Mrs. White I found the exact opposite. She was reserved and modest and seemed to have no desire at all to call attention to herself as someone great or to her authority.’ "Some months after these visits, at the funeral of Mrs. White in Battle Creek, I met D. M. Canright again. There were six of us men who stood as a guard of honor while the people passed through the tabernacle to view Mrs. White as she lay in her plain casket. I noticed Mr. Canright as he came down the aisle toward the rostrum. He stopped at the casket and looked at Mrs. White quite a while. He reached down and took hold of her right hand, which had done all that immense amount of writing. "Later I asked him, ‘Now that she is dead, what do you really think of Mrs. White?’ "He replied, ‘She was a most godly woman All her life she lived near to Jesus and taught the way of living faith. Anyone who follows her instructions will surely be saved in the kingdom of God."—L. H. Christian, quoted in "Fruitage of Spiritual Gifts," pages 51-53. Canright’s anti-Sabbath book came out late in 1915. Early the next year, a friend of his from former days, Elder J. H. Morrison, received a copy of it from Canright with a note to examine it and tell him criticisms. Morrison was about to depart to Battle Creek for the Lake Union Conference Session, which was scheduled for March 7-12, 1916. Morrison replied that he would be happy to look over the book, and he asked Canright to attend the Session with him. This Canright gladly did, and they spent a happy time there. Returning to Battle Creek the two visited together a little longer, and then Canright left Morrison’s home in the growing darkness of the night. A few minutes later, D. M. approached the local Baptist Church with the intention of walking down the outside steps to the room in the basement that the Baptists kept with a desk for him to use whenever he so desired. He had not been there for some time and did not realize that extensive remodeling of the building was taking place. The outside steps had been removed. It was Friday evening, March 10, 1916. Arriving at the church, with the key in his hand, he fell down through the opening in the darkness, landed on rubbish strewn over the basement floor, and remained there until the following Sunday morning when he was discovered by the janitor. He was first taken to the city hospital, then transferred on Monday morning, at his request, to the Sanitarium. He experienced intense suffering for months, during which time his leg was amputated. Gradually he recovered. Early in June he was taken by ambulance to the home of his daughter, Genevieve, in Hillsdale, Michigan. She was a Christian Scientist, so didn’t have much thought for medical care, but he remained there, in a wheel chair, for the remaining three years of his life. With the help of an ex-Adventist minister, he assembled the rest of his denouncements of Ellen White for his last book, "Life of Ellen White." In July of 1918, it was accepted by the publisher, and in July of 1919 it came off the press. But two months before then, Dudley Mervin Canright died of a paralytic stroke at Genevieve’s home. A miserable thirty-two years, since he finally left the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1887, had come to an end. As far as D.M. Canright, himself, was concerned, it could well be said: It would have been better if he had never been born. |