|

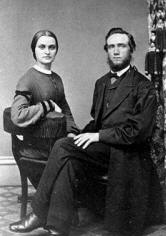

D. M. CanrightTHE MAN WHO BOARDED THE PHANTOM SHIPPart 2 Following two years of evangelistic work in California, Canright was called back East and continued work. At the 1876 General Conference session he was one of three men elected to the General Conference Executive Committee. There is no question but that the brethren tried to have confidence in Dudley. Re-elected at the next session, he served two years on this, the highest committee in the denomination. In view of events that were soon to take place, I will mention that James White, S.N. Haskell, and D.M. Canright were on this committee. In a letter dated August 13, 1877, he wrote to Elder White that "we are all well and of a good courage." But the truth of the matter was that in Massachusetts all was not well. Tiny Fred and his sister, Genevieve, were recovering from the measles and Lucretia was growing weaker. A month after the letter was written she suffered a lung hemorrhage. Tuberculosis was setting in, from which she was later to die. By February of 1878, recognizing that she needed help, he took her to the Battle Creek Sanitarium. In Battle Creek he busied himself with visits to leaders and committee work. Then in early March he was elected president of the newly created Sabbath School Association, while Elder White took a fatherly interest in Lucretia and frequently arranged for friends to take her for pleasant carriage rides in the country. Large-hearted Martha Amadon, wife of the superintendent of the Review and Herald Publishing Association, took the two children and lovingly cared for them. At this time Dudley was beginning to eye the presidency. Elder James White was again in poor health and in need of rest, and obviously someone with unusual abilities would be needed to take his place if he passed off the scene of action. When it was learned that Elder White was planning for another trip to Colorado for rest, Canright determined that he would accompany him, although friends urged him to remain near his sick wife. But leaving her, he made the long journey to Colorado with him. While there Elder White concentrated on hiking and writing. And soon after, Elder W.C. White (their eldest son), arrived, and later wrote of the experience: "Elder Canright was in Battle Creek to be near his wife, who was dying with consumption. Suddenly he decided to go to Colorado with Father, for his health. And he went, contrary to the pleadings of the friends of his wife, and spent several weeks in the mountains near Black Hawk, with us. "At that time my father was President of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. His associates on the Committee were S.N. Haskell and D.M. Canright. Father’s health was uncertain, and it was expected that one of these associates would be the next President. "My wife and I were surprised and shocked to observe the diligence and enthusiasm with which Mr. Canright improved every opportunity to exalt himself, and to discredit Elder Haskell in my father’s estimation. In the good providence of God my father’s health improved, and he was re-elected, and there was no contest over the office of President."—W.C. White. Letter to E. W. Barr. July 26, 1920. It was early in August that word reached Canright that his wife had suffered a relapse and was rapidly failing. On the 12th he headed back to Battle Creek. He had been away from her for six weeks. Deep was her love for her husband, and she regretted that soon she would be parted from him. One day, when he took her out in the country in a carriage, she showed him the spot in the cemetery where she wanted to be buried. Dudley had arrived in Battle Creek just in time to attend the General Conference Session, to be held there that year. During its proceedings, the constituency voted James White, J. H. Kellogg and Sydney Brownsberger as the new members of the General Conference Executive Committee. Canright was elected to the Presidency of the Ohio Conference, with the understanding that he would have to spend part of the time with his invalid wife at Battle Creek. At about this time, he did some serious thinking, and mentioned some of his thoughts in a letter to Ellen White: "I started in [the work] very much behind in everything. When I was twenty-one I did not know anything and had nothing. I have had everything to learn since . . Lucretia never was naturally a student. She is wholly a motherly, domestic woman, loves to stay at home and simply take care of her own household duties, and family, hence it has always been very hard for her to enter into my feelings and to take an interest in my studies or work. I have no doubt that I did not realize how much stronger physically I was then she, how much more natural energy I possessed, than she. Hence I have made it pretty hard for her. . I am very glad, Sister White, for the advice you give me from time to time, and I do try to profit by it; but you know how hard all habits are to break off; we need line upon line. I hope you will not get discouraged at the little improvement. —D.M. Canright, Letter to Ellen White, November 26, 1878. Such a written communication is of special interest in view of later statements on his part, after his departure from the faith, that Elder and Mrs. White had treated him in an unkind and cruel manner. Many of Canright’s later charges (such as his statement that Ellen White ate pork at the table with him) would be keyed to the degree of honesty that the man had. But we have a number of evidences that, after his apostasy, a strange power had taken control of him and that, among other things, simple honesty had fled from his heart. A month later his wife wrote him: "The Lord blesses me with peace of mind . . The only thing lacking is your presence . . If I can never be with you in your work again, I do not want to feel that I have hindered you, however much the natural feelings have to be sacrificed."—Lucretia C. Canright, Letter to her husband, quoted in "Review," December 12, 1878. Her last-known letter was dictated on February 25, 1879 from her hospital bed. It was written to one of her closest friends—Ellen White. Expressing thankfulness for the messages of comfort and assurance Ellen had sent in the year and a half of her confinement, and for the years of love and continued interest before that. She said that she felt the love and mercy of God and was resting in it. In closing she called Elder and Mrs. White her "dearest friends." Her nurse added a postscript to the letter: "She is very weak, but ever patient, uncomplaining, and even cheerful . . Your words were appreciated, I can assure you. She expresses much gratitude and affection for the kindness and interest you and Brother White have extended to her. With love and haste. (Signed) Mary Martin." On Sabbath, March 29, near sunset, Lucretia Canright died. She was thirty-one years old. The burial was at Oak Hill Cemetery in the spot she had chosen. Canright was now at the height of his influence. At the dedicatory service for the Battle Creek Tabernacle (April 20, 1879). He was one of those who took part in the ceremonies, along with such men as John N. Andrews, George I. Butler and Uriah Smith. (The White’s were not in Battle Creek at the time.) His pay was equal to that of the General Conference President—$12 a week. In August the Ohio Conference elected Canright President. In addition to supervising conference executive work, he also carried on meetings in many different localities. It was at this time that a Drury W. Reavis came to the Ohio Conference. A student at Battle Creek College, Canright had asked him to help promote the Sabbath School work in Ohio. (Later, Reavis was to work for many years in the offices of the Review and Herald Publishing Association.) In Ohio, he came to be an especially close confidant of Canright. His experiences in Ohio were later written up in a book which he published under the title, "I remember." Here are some pertinent selections from this book: "I felt highly honored by being selected by Elder Canright to do special Sabbath school work in Ohio. This appointment proved to be the beginning of a very close, mutual, friendly association." "Elder Canright talked freely with me about everything in which he was interested, about his personal difficulties, about his past trials and sorrows, and of his future hopes and plans. He seemed to find consolation in going over these things with me." "The elder was remarkably bright, and grew rapidly from his humble beginning, through the blessing of God, and the power of the message he proclaimed with Heaven-bestowed ability. He was so greatly admired and openly praised by our workers and the laity, that he finally reached the conclusion he had inherent ability—that the message he was proclaiming was a hindrance to him rather than the exclusive source of his power." ---"I Remember," page 117. In the "Review" for September 13, 1881, Canright mentioned that he encountered many trials in the summer of 1879. One of these was a worsening throat condition. On May 4, 1880, he wrote to Ellen White about this problem: "You know the difficulty I have had in my throat, and with my voice, on account of bad habits of speaking. From the instruction I have had since last fall, in Elocution, I believe I can get over that and learn to speak properly and easily. If not, it is certain I will have to abandon speaking sooner or later. . In the middle of the summer I propose to spend a few weeks with Hamill in Chicago. The way is open for me to do this now, and if I lose this chance I may never get it again. I feel as though it was about life or death with me."—D.M. Canright, Letter to Ellen White, May 4, 1880. ("Elocution" was the study of a variety of artificial intonation and gesturing patterns.) (Read 4 Testimonies, 605-606.) Better methods were available to Dudley: total dedication of the heart, thoughts, and goals; a humble but firm reliance upon the Holy Spirit for guidance and enabling: a careful use of diaphragmatic breathing—could restore his voice and do for him what no human device could do. However, in spite of "elocution," a powerful delivery of God’s Word, could surmount the flaws of what he was taught in Chicago.) And so it was that in the summer of 1880, Canright went to Chicago to study elocution in Hamill’s school. But the worldly pride of performance, so common to schools of this type, plus the contacts that Canright had that summer and early fall with large non-Adventist church audiences, deepened his desire to rise to greater acclaim and honor than he could have in our small denomination. What happened next is probably one of the most significant incidents in the life of Dudley Canright. Reavis describes what took place. During the time Canright was still President of the Ohio Conference. "During the summer and fall of 1880, immediately after graduation. I, with other students from Battle Creek College, attended Professor Hamill’s School of Oratory in Chicago. Elder Canright, inoculated, at heart, with a belief that through a thorough study in, and mastery of, ‘expression’ he could accomplish his consuming desire to be a popular public speaker [on non-doctrinal topics before non-Adventist audiences] joined us: and because of my former pleasant association with him, I became his ‘critic’ as he lectured, upon invitation, through the influence of the School of Oratory, in many of the largest popular churches in Chicago during the summer vacation of the pastors of these churches. "In these lectures he applied the oratorical principles taught in the school, and needed a critic versed in these principles, to follow him in his lectures and later point out his misapplications, and of course to compliment him on all that were rightly applied. He had more invitations than he could possibly accept: so he selected the largest and most popular churches. "One Sunday night, in the largest church of the West Side, he spoke on ‘The Saint’s Inheritance’ to more than 3,000 people, and I took a seat in the gallery directly in front of him, to see every gesture and to hear every tone, form of voice, emphasis, stress, and pitch, and all the rest. But that was as far as I got in my part of the service, for he so quickly and eloquently launched into this, his favorite theme, that I, with the entire congregation, became entirely absorbed in the Biblical facts he was so convincingly presenting. I never thought of anything else until he had finished. "After the benediction I could not get to him for more than half an hour because of the people crowding around him, complimenting and thanking him for his masterly discourse. On all sides I could hear people saying it was the most wonderful sermon they had ever heard. I knew it was not the oratorical manner of the delivery, but the Bible truth clearly and feelingly presented, that had appealed to the people—it was the power in that timely message. It made a deep, lasting impression upon my mind. —I saw that the power was all in the truth, and not in the speaker. "After a long time we were alone, and we went into a beautiful city park just across the street, which was almost deserted because of the late hour of the night, and sat down to talk the occasion over and for me to deliver my criticisms. But I had none for the elder. I frankly confessed that I became so completely carried away with that soul-inspiring Biblical subject I did not think once of the oratorical rules he was applying in its presentation. Then we sat in silence for some time. Suddenly the elder sprang to his feet and said, ‘D. W., I believe I could become a great man were it not for our unpopular message!’ "I made no immediate reply, for I was shocked to hear a great preacher make such a statement, to think of the message, for which I had given up the world, in the estimation of its leading minister, being inferior to, and in the way of, the progress of men, was almost paralyzing. Then I got up and stepped in front of the elder and said with much feeling, ‘D.M., the message made you all you are, and the day you leave it, you will retrace your steps back to where it found you.’ "But in his mind the die was evidently cast. The decision had doubtless been secretly made in his mind for some time, but had not before been expressed in words. From that night the elder was not quite the same toward our people and the work at large. "—Drury W. Reavis, "I Remember," pages 118-119. In referring elsewhere in this book to Canright’s later defection from the Church, he makes the following comments. Remember, they come from one who at one time was very closely acquainted with D.M. Canright: "His estrangement began and developed through harboring that greatest seductive thing that finds its way into some human hearts, which I name an abnormal desire to be great, —not great in the true meaning of the word, but great only in the estimation of people—to be popular."—"I Remember," page 117. "The feeling that being an Adventist was his principal hindrance increasing as time passed, he finally reached the conclusion that he could achieve his goal of fame through denouncing the unpopular doctrines of the denomination, and he finally worked himself out of the denomination." —"I Remember," page 119. An unseen spirit was working on Canright’s mind, leading him, through an overmastering thirst for greater fame and compliments, to imagine that the only way up was out. Somehow, he felt, he must leave the Advent people and the narrow path in order to receive all that recognition and honor that he felt was his due. Late in September, the Ohio campmeeting convened, and its President, D.M. Canright made his way there, fully intending to decline a request to continue on as its president even though offered. And this he did, but the brethren urged the matter until he agreed "to act as President with the privilege of being absent from the Conference a share of the time." ("Review," September 30, 1880.) But soon thereafter he resigned the post, and George I. Butler was later to report: "In October of 1880, he had another backset. He became discouraged—we never knew from what special cause—and ceased to preach." ("Review Extra," December, 1887.) Reavis knew why, but he told no one. Canright had heard whispered voices telling him of the great things he could attain by leaving the Advent work. In obedience, he left,—and moved on up to the position of elocution teacher for a worldly school. But although Reavis was to say nothing for a number of years to come, the messenger of the Lord heard about the problem—and the reasons—through another Source. On October 15, 1880, she wrote a letter to Canright that is dramatic, both in its clarity and appeal: "I was made sad to hear of your decision, but I have had reason to expect it.. Satan is full of exultant joy that you have stepped from beneath the banner of Jesus Christ, and stand under his banner. He sees in you one he can make a valuable agent to build up his kingdom. You are taking the very course I expected you would take if you yielded to temptation. "You have ever had a desire for power, for popularity, and this is one of the reasons for your present position. But I beg of you to keep your doubts, your questionings, your skepticism to yourself. The people have given you credit for more strength of purpose and stability of character than you possessed. They thought you were a strong man, and when you breathe out your dark thoughts and feelings, Satan stands ready to make these thoughts and feelings so intensely powerful in their deceptive character, that many souls will be deceived and lost through the influence of one soul who chose darkness rather than light, and presumptuously placed himself on Satan‘s side, in the ranks of the enemy. "You have wanted to be too much, and make a show and noise in the world, and as the result your sun will surely set in obscurity. Every day you are meeting with an eternal loss.. You are nursing a feeling which will sting and poison your soul to its own ruin.. Your ambition has soared so high, it will accept of nothing short of elevation of self. You do not know yourself. What you have always needed was a humble, contrite heart. "God has chosen you for a great and solemn work. He has been seeking to discipline, to test, to prove you, to refine and ennoble you, that this sacred work may be done with a single eye to His glory which belongs wholly to God. What a thought that God chooses a man and brings him into close connection with Himself, and gives him a mission to undertake, a work to do, for Him. A weak man is made strong, a timid man is made brave, the irresolute becomes a man of firm and quick decision. What! is it possible that man is of so much consequence as to receive a commission from the King of kings! [Here, Dudley, is true greatness.] Shall worldly ambition allure from the sacred trust, the holy commission? Whoever follows Christ is a colaborer with Him, sharing with Him the divine work of saving souls. If you have a thought of being released from it because you see some prospect of forming an alliance with the world which shall bring yourself to greater notice, it is because you forget how great and noble it is to do anything for God, how exalted a position it is to be a co-laborer with Jesus Christ, a light bearer to the world. "You will have a great conflict with the power of evil in your own heart. You have felt that there was a higher work for you, but, oh, if you would only take up the work lying directly in your path, and do it with fidelity, not seeking in any way to exalt self, then peace and joy would come to your soul, purer, richer, and more satisfying than the conquerors in earthly warfare . . I now appeal to you to make back tracks as fast as possible; take up your God-given mission, and seek for purity and holiness to sanctify that mission. Make no delay; halt not between two opinions. If the Lord be God, serve Him; but if Baal, serve him. You have the old lesson of trust in God to learn anew in the hard school of suffering. Let D. M. Canright be swallowed up in Jesus . . Now, Elder Canright, for your soul’s sake grasp firmly again the hand of God, I beseech you. I am too weary to write more. God deliver you from Satan’s snare is my prayer. — Ellen White, Letter to D.M. Canright, October 15, 1880 (published in 2 Selected Messages, pages 162-168). G.I. Butler later wrote of this time in Canright’s life: "When he gave up preaching he began to lecture on elocution, and traveled considerably in Wisconsin and Michigan, holding classes. He told me himself that for a time he then ceased to observe the Sabbath. . He thought then quite seriously of preaching for the Methodists.. But the Elder‘s conscience troubled him greatly at times. He wrote me, desiring to see me and have a long talk. We met in Battle Creek the following January [1881], and had some fifteen hours’ conversation. "—G.I. Butler, ‘Review Extra," December, 1887. And eight months later, Canright, himself, was to speak about this experience. He wrote it for an article, entitled "Danger of Giving Way to Discouragement and Doubts," that was published in the "Review" on September 13, 1881. Here are his words: "About a year ago I became wholly discouraged. It seemed to me that my work amounted to nothing, and that I might as well give up.. I passed four months in this way. I looked in every direction to see if there was not some mistake in our doctrine, or if I could not go some other way. But I could not see why, according to the Bible, the great pillars of our faith were not sound.. I found that my faith in the Advent doctrine was so strong that I could never believe anything else; so I gave up trying to.. "So . . I came to Battle Creek - . and freely talked over with Eld. Butler, Bro. and Sr. White, and others, my difficulties and trials. They did all they could, and all I could ask, to assist me.. As I took hold again to labor, and tried to look on the side of courage and faith in the work, I found my difficulties disappearing, and my former interest and confidence in the message reviving, till now I feel clear and satisfied in the work again . . If the Bible does not plainly and abundantly teach the doctrines of the third angel’s message, then I despair of ever knowing what it does teach . . I have no further doubt as to my duty and the work of my life. As for years in the past, so in the future, all that I am and have shall be thrown unreservedly into this work. . I humbly trust in the grace of God to help me keep this resolution. "One who has not experienced it, can have little idea how rapidly discouragement and doubts will grow upon a person, when once they are given way to. In a short time, everything seems to put on a different color. . Of course I regret now that I gave way to discouragements and doubts. but I think I have learned a lesson by it which I shall not need to learn again as long as I live. "—D.M. Canright, "Danger of Giving Way to Discouragement and Doubts," in "Review," September 13, 1881. The merciful forgiveness of God is wonderful, and so is the compassionate kindness of the brethren in the Church. Elder White happily wrote to Ellen on February 4, 1881, that "Elder Canright is doing splendid in getting on the track." He had taken him on a trip to New York, and once back in the saddle of preaching the Advent message, Dudley had come back to himself. In a follow-up letter, penned on February 17, Elder White wrote to his wife: "I am glad to report him on better ground than ever before. Poor C[anright] has been crowded too hard, but God is rescuing him." It was while he had most recently left God’s work for worldly greatness that Canright had met a Miss Lucy Hadden of Otsego, Michigan. At the time he was holding elocution lectures in that area. He fell in love with her and they later married. By early April of 1881, back in the Adventist ministry, he took his new friend to meet the Whites. The two were married on April 24. He was forty; she was twenty-five. This may have been one of the last marriages that James White performed; he died on August 6 of that year. Lucy appeared quite friendly but she never had that closeness to the Whites and to the Church that Lucretia had had. Up again, down again, is the story of Dudley Marvin Canright. The problem was not the doctrinal positions of the Church; the problem was the man himself. Having returned to the work, he vigorously entered upon evangelistic work again, but that is all he was now,—just an evangelist. Other workers could rejoice with the angels over every sheep recovered from a world of sin, but Dudley gave his attention to other matters: He was no longer the respected conference president, executive officer, and leader among men. He was little more than a soul winner. Part 3 |